BUS STORY # 450 (Black Sheep)

|

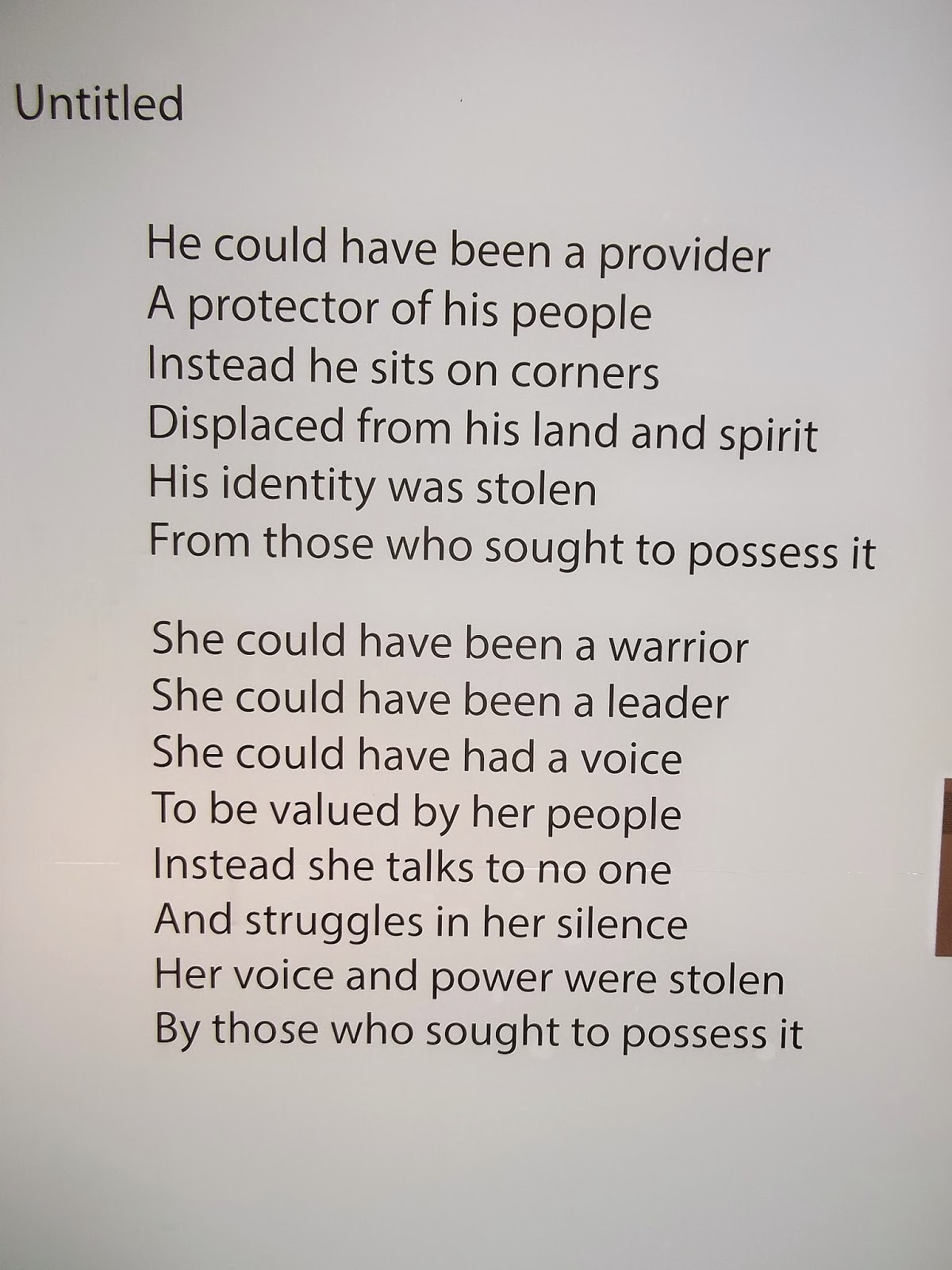

| Poem by Anna McKenzie. (Photo by Busboy.) |

Last summer, in Vancouver, our good friends Will and Carol took us to the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. The museum specializes in “First Culture” -- what we call “Native American.” Among the displays we saw was an installation of mixed media presentations of the experiences of many young, Native, urban-dwellers.

One of those installations was the poem featured in the photo at the top of the page. The author explained she had written the poem on a bus after seeing “an Indigenous brother” asked by the driver to get off the bus because he was inebriated. I took the photo because a bus was part of the story. Months later, I saw the same scene play out here in Albuquerque with two different Native Americans.

He’s tall, trim, Native American, with long hair down his back that could use a wash and some combing. Blue, long-sleeved sports shirt, worn denim jeans.

It’s mid-morning on the bus, and he’s inebriated. Not stumbling, slurred-speech inebriated. He’s a friendly drunk, perched on the edge of the bench seat across from the driver, talking away, his movements a little too exaggerated, his voice a little too enthusiastic.

After a while, he turns his attention to a rider sitting in the aisle seat of the first row.

This rider is a kid, a large kid, with thick, short black hair, sunglasses, white earbuds, big white T-shirt and basketball shorts. The legs coming out of the shorts are small and short for his size. I think the drunk is thinking the same thing I am: a fellow Native.

He asks the kid if he’s going to school. The kid doesn’t respond.

He asks again, leaning toward the kid.

The kid removes his earbuds. I can’t hear his voice, but the way he turns his head suggests he’s asking if the guy is talking to him.

The way he moves his head is also how I sense he is asking reluctantly, as if having to deal with the earbuds’ failure to protect him.

The guy asks again if he’s in school. No trace of irritation or impatience in his voice at having to repeat the question.

The kid shakes his head yes. One slight nod.

The guy asks if he’s Navajo. Before the kid answers, he adds, “I can speak some Navajo.” And he speaks several sentences which sound like they could be Navajo.

The kid shakes his head no.

I sense the kid is acutely uncomfortable.

The guy tries another set of phrases. The kid shakes his head no. I’m taking this as “No, I don’t understand” rather than the answer to some question he’s being asked.

Nice kid, a polite kid, maybe Navajo, maybe Pueblo, but mostly a teenager just trying to fit in here in the city, just riding the bus to school and minding his own business, you know? How many other things feel worse than being publicly embarrassed when we’re adolescents?

It is right here that I find myself remembering the display in Vancouver. But there is a difference between the two Native observers. The young woman in Vancouver was older, more experienced, more self-aware and self-confident. And she was able -- afterwards -- to articulate her experience:

The kid's not there, not yet, not now. If he’s having any thoughts, I’d guess they’re in the form of a prayer: “Please, make me invisible.”

And then a miracle. The bus is stopped, and a woman with a walker is making her way onto the bus.

The buzzed guy stands up, steps back, and with a sweep of his right arm, offers the entire bench to the woman. She says thank you and maneuvers herself into a seat. He stays standing until she is seated, then takes the aisle seat in the first forward-facing row.

He introduces himself and offers her his hand.

She declines, explaining she doesn’t shake hands.

(The kid is now invisible!)

He tries again.

She declines again.

He backs off, waving both hands in the air and saying, “That’s cool, that’s cool.”

At the next stop, the driver turns and tells him this is his stop.

This is his stop?

This is his stop. This is where he gets off.

And he does.

As the bus pulls away, the driver calls out, “Sorry about that, folks.”

I last see the guy out on the sidewalk, looking around trying to figure out where he is. The kid is looking straight ahead. All of us on board, except maybe the kid, have only the vaguest idea of what “led him to this place of darkness,” and probably none of us are thinking “There but for fortune.” I know I don’t until I’m telling this story.

__________

Here is a better shot of Anna McKenzie, the author of the poem at the top of the page: